Given the present-day popularity of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail, often shorthanded as the A.T., it is hard to imagine that it may never have come together if not for a dedicated group of Hudson Valley and NYC-based volunteers. Anyone who has hiked the trail, whether by section or its entire length, is following in the footsteps of the Hudson Valley “trampers” who carved out the very first miles of the famed trail.

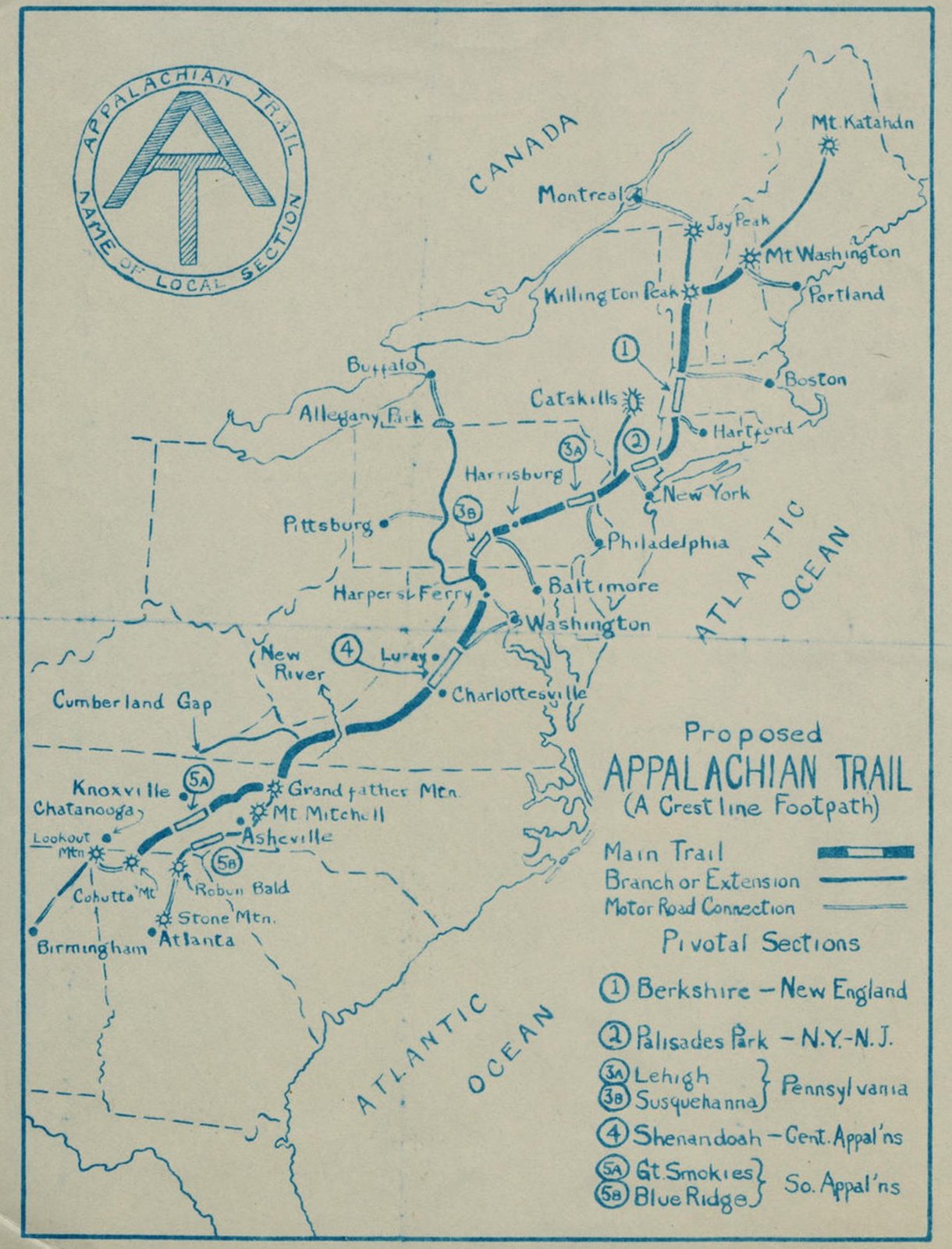

The concept of a multi-state linear park is credited to Benton MacKaye, a Harvard-educated forester and regional planner who envisioned a linked series of trails where urban East Coast residents could immerse themselves in nature. His 1921 plan, “An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning,” called for a series of “recreation camps” or sustainable communities along the Appalachian Mountain range. MacKaye envisioned a walkable corridor within a day’s drive for more than half the population of the United States, merging urban and wilderness ideals to overcome “the hecticness of the one, the loneliness of the other.”

Though MacKaye’s vision was clear, plans for actually creating such a trail were vague. He advocated for local, volunteer-based oversight, which posed a problem in states without a dedicated volunteer workforce at the ready.

Meanwhile, in New York, “tramping” or hiking was a popular pastime, and volunteers were already constructing new trails within a day’s drive of New York City. Major W.A. Welch, chief park engineer and general manager of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission, welcomed local and NYC-based tramping clubs to the Harriman and Bear Mountain State Parks and encouraged them to create new trails with the goal of making the parks more accessible to the public.

Partnering with these volunteers and with Raymond Torrey, editor of the popular “Outing” section of the New York Evening Post, Welch helped to form the volunteer-driven Palisades Interstate Park Trail Conference (later known as the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference), which soon turned its attention to MacKaye’s Appalachian Trail plan.

Beginning in 1922, Welch and Torrey scouted and marked out a route for the Appalachian Trail through the parks with lengths of cotton string, and volunteers broke ground using shovels, hatchets and pruning shears to clear the way. In one of his many columns devoted to what he called “The Long Brown Path,” Torrey shared that workers could barely keep up with the public’s desire to explore the new trail, noting that in one instance while crews were marking the path along West Mountain in Harriman “the string had not been up two hours when eleven persons came along it.”

Welch designed trail markers, a copper square with an embossed “A-T” symbol surrounded by the legend “Appalachian Trail-Palisades Interstate Park,” and the Palisades Interstate Park Commission provided thousands of these markers for volunteers to place. (As the Trail expanded into other states, they were redesigned with the “Appalachian Trail: Maine to Georgia” insignia that is still used today.) Ever-popular Bear Mountain State Park was deemed an interpretive section of the Trail where hikers could learn more about the region’s plants and animals.

Accordingly, the A.T. was eventually routed through the Trailside Museums and Zoo in that section.

The opening of the Bear Mountain Bridge in 1924 allowed the A.T. to continue eastward through New York into Connecticut, while rapid expansion from Harriman State Park to Greenwood Lake brought the trail to New Jersey and points south. In 1925, the Appalachian Trail Conference (today the Appalachian Trail Conservancy) was formed in Washington D.C. to oversee management of the Trail along its entire length, with Welch serving as the first chair and Torrey as treasurer.

Volunteers all along the East Coast worked tirelessly on the growing trail and the nearly 2,200-mile footpath from Springer Mountain in Georgia to Mount Katahdin in Maine was declared complete on August 14, 1937.

At just 91.3 miles, the A.T. in New York is relatively short but contains unique experiences. Along these miles hikers pass by industrial ruins, abandoned mines, remnants of Revolutionary-era forts and through the grounds of a monastery. At the summit of Bear Mountain (1305’), travelers experience expansive views of the Hudson Highlands, the Hudson River and distant glimpses of the New York City skyline, while at the base they encounter the trail’s lowest point when passing the Trailside bear den (124’ above the Hudson River).

Today, the Appalachian National Scenic Trail remains the longest pedestrian-only footpath in the world and sees upwards of three million visitors a year. Approximately 3,000 people attempt to thru-hike the Trail each season.

Now in its centennial year, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy continues to work in partnership with a large volunteer network to protect the trail while offering guidelines for sustainable practices and promoting outdoor ethics.

Over time, the original Hudson Valley section of the A.T. has been rerouted and redesigned to protect against erosion and allow access for all abilities. But while the A.T. through New York may have changed over time, the volunteer effort that has kept the trail maintained and accessible to the public for more than a century has stayed constant.