Block ice was once a can’t-live-without-it piece of American culture. For about a century beginning in the 1830s, keeping food and beverages cold in and around New York City depended on this ice — and on harvesting it from the Hudson River and nearby lakes. Then, with the advent of artificial refrigeration (combined with worsening pollution of the river), an entire industry melted away.

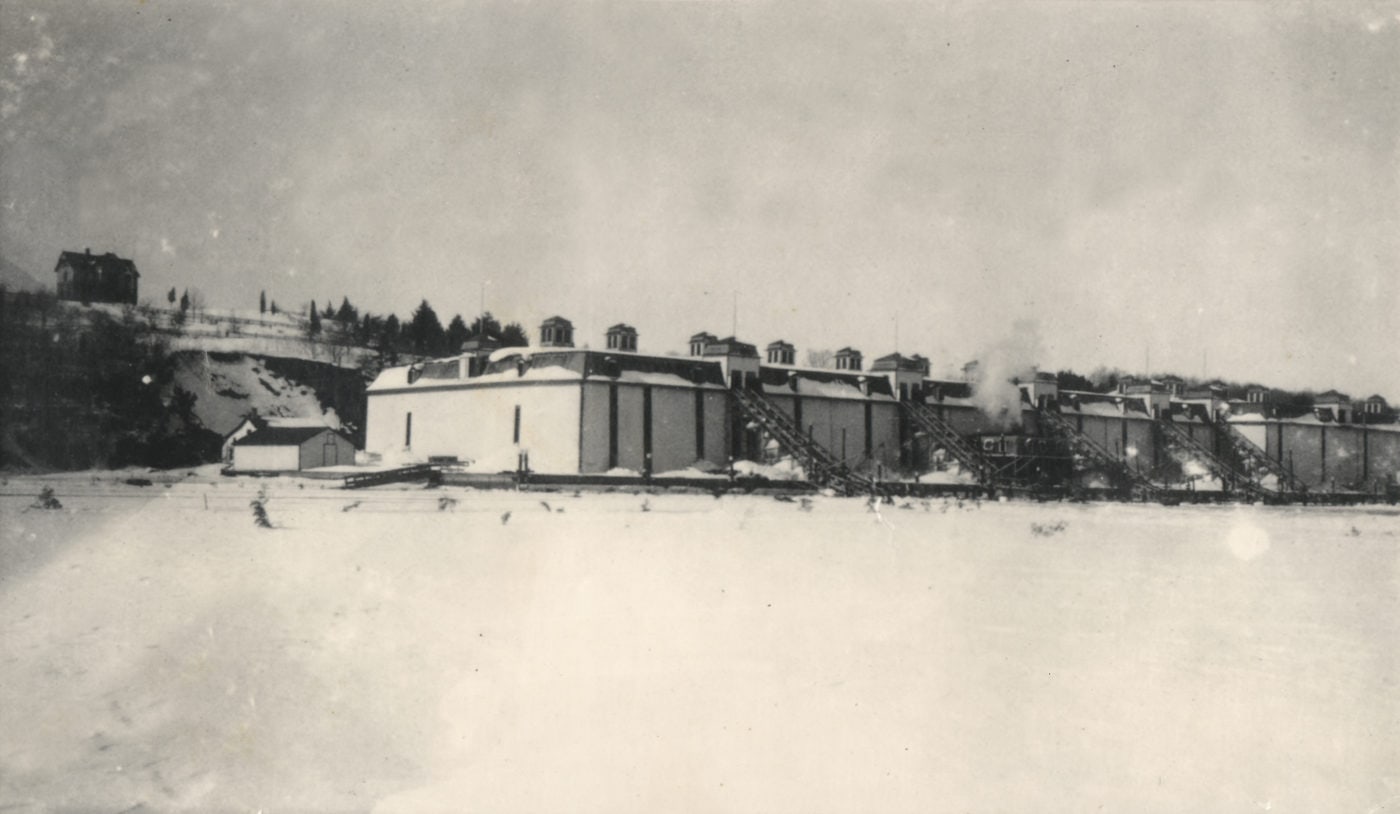

At its height in the 1880s, an estimated 20,000 workers harvested blocks (also called “cakes”) of ice for storage in 135 specially built structures lining the river between Poughkeepsie and Albany. According to a retired tugboat captain, “A traveler on the upper Hudson would never be out of sight of an ice house.”

Today, few traces remain of these huge, windowless warehouses (“more conspicuous than ornamental,” opines an early 20th-century guidebook). Two exceptions: the foundations of one at Falling Waters Preserve in Saugerties and the shell of a powerhouse critical for operations of another at state-owned Little Nutten Hook in Stuyvesant. (Both sites were preserved by Scenic Hudson.)

Sparked by the Erie Canal

Ice harvesting on the Hudson owed its existence in large part to the Erie Canal. The opening of this gateway to the West in 1825 facilitated the delivery of a widening array of goods requiring preservation to New York City markets and homes. This profusion of perishables, on top of a population boom in the metropolis, increased the need for keeping things cool and a local supply of ice to make it happen.

The region’s ice industry actually was born atop the Palisades, at Clarkstown’s Rockland Lake (now a popular state park) in 1831. Harvesting began in January or February, whenever its spring-fed waters hardened to a point where men and horses could stand on it — somewhere between 12 and 15 inches thick. First, workers traced a grid on the ice, each rectangle measuring about 22 by 32 inches. Then using horse-drawn cutters and handsaws, they separated the ice into individual blocks. After opening a channel leading to the ice house, the cakes were floated to the shore and conveyed inside.

Stacked and smothered in sawdust or hay for insulation, the ice could last for months, sometimes up to a year. It attracted the highest prices in the summer, when demand peaked. Then it would be shipped southward on flat-hulled barges built so their holds sat low in the water, allowing the river to cool more of the ice. Though most of the valley’s frozen bounty satisfied the needs of the New York market — estimated at about 2.5 million tons annually in the 1880s — some traveled as far as the West Indies and South America.

Big, tall and bright

This same, simple harvesting process took place at all of the Hudson River’s ice houses, the lion’s share located between Catskill and Albany — well beyond the reach of saltwater from the Atlantic Ocean’s incoming tides. The bigger operations utilized moving belts and steam-powered elevators to convey the blocks inside the ice house and hoist them to upper floors; smaller businesses relied on muscle power.

The wood-framed ice houses, up to six stories tall and painted a bright white to reflect the sun’s intense rays during the summer, held varying numbers of blocks. The Mulford ice house at Falling Waters Preserve stored about 10,000 pounds. Big as a football field, the Scott ice house at Little Nutten Hook held five times as much. The ice houses were so large and ubiquitous that sailors in heavy fog could plot a safe course by sounding a bell or horn and listening for echoes from the buildings. Surrounding them were an array of ancillary structures, including tool houses, horse barns and a power house to drive the conveyer or elevator systems.

The biggest threat to profits? Melting. Operations with well-insulated ice houses and barges managed to keep losses to about 20% of their annual harvest. Most companies counted on seeing 50% of their product turn into water.

Industrial melting pot

Primarily a seasonal industry, ice harvesting provided a second income for farmers, brickyard workers, sailors and river pilots, and others whose main jobs depended on more sultry weather. In the 19th century, they earned about $1 per day, and an additional $2 if they brought a horse or donkey (equal today to $25 and $50, respectively).

The work wasn’t for the faint of heart: In addition to subzero temperatures and high winds, workers were susceptible to falling through the ice, being hit with 100-pound blocks or becoming ensnared in the conveyer machinery — all accidents recorded in local newspapers. To prevent being swept under the ice by swift currents, many workers carried 10-foot poles, which they held parallel to the river’s surface. If the ice broke beneath their feet, it was hoped the pole would span the hole, allowing them to hold on until help arrived.

Despite its dangers, ice harvesting was a great melting pot, one of the few valley industries that hired men and women, African Americans, and Italian and Irish immigrants. Occasional labor disputes, like one that attracted 500 “tough and determined” laborers to Catskill in 1875, brought them even closer together.

As several firms bought up locally-owned ice houses, labor strife heightened, and so did complaints of price-gouging. By the early 20th century, the industry giant was the Knickerbocker Ice Company. When Thomas Edison filmed its operations at Rockland Lake in 1902, its three ice houses there held nearly 100,000 tons of blocks alone.

Knickerbocker and its competitors hung on for another 20 years, until refrigerators began replacing iceboxes in New Yorkers’ homes and dry ice emerged as a cheaper, more easily obtainable and longer-lasting alternative for transporting perishable goods. Even prior to that, the influx of raw sewage in the river (a carrier of typhoid) had become a growing concern. A newspaper report from 1909 notes that the state Department of Health had condemned 41 ice houses around Albany, Troy and Rensselaer because of increasing pollution.

By 1930, the valley’s ice harvesting industry had run its course. For a time, some of the ice houses gained new life as mushroom farms, their dark interiors providing perfect conditions for growing fungi. But eventually they all succumbed to fire, demolition or benign neglect.

There’s been modern-day interest in this aspect of our heritage — several upstate New York towns have traditionally held ice harvesting festivals and historical demonstrations, at least until the last pandemic-interrupted year or two. Hanford Mills Museum, in East Meredith near Oneonta, has been putting on festivals for three decades, and just just held this year’s virtually. Tully, on Green Lake near Syracuse, held its own festival until at least 2019. Of course, whether some of those events will return after COVID-19 remains to be seen.

For now, this once-vital cog in the region’s economic life exists today mostly in grainy photographs, a couple of ruins and Edison’s flickering film.