A 1999 survey of scholars ranked Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech as the most important American speech of the 20th century. Delivered from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on August 28, 1963, King’s stirring words continue offering hope to those seeking equal opportunity and justice for all.

Interestingly, remarks Dr. King made at both ends of the Hudson Valley — at Albany in 1961 and New York City the following year — offered a preview of this iconic speech.

“A wake-up call to Albany”

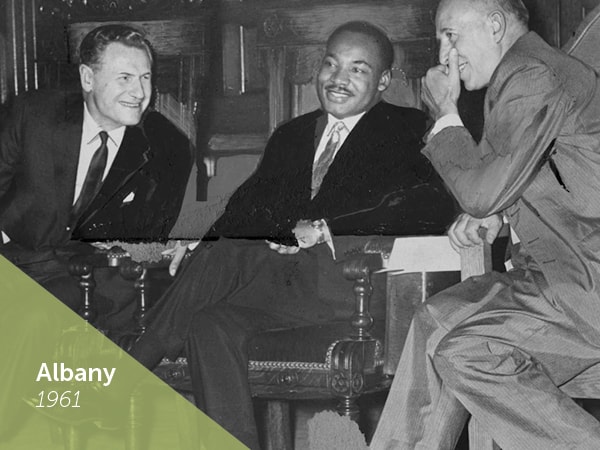

In 1961, the 32-year-old Atlanta preacher had yet to become the face of the Civil Rights movement, but his concept of non-violent confrontation, combined with his unmatched eloquence, had begun attracting national attention. As racial tensions in the South reached a flashpoint that spring, with the assault of Freedom Riders in Montgomery, Alabama, King journeyed north to speak at Albany’s Wilborn Temple, a fundraiser for his Southern Leadership Conference.

On the evening of June 1, close to 1,000 people filled the church’s seats, as well as its aisles, to welcome him. “I remember it was so jampacked there was no place to put anyone else,” attendee Solomon Dees told a reporter for the Albany Times Union nearly 60 years later. (The event came close to being cancelled when King missed the connecting train in New York City. Saving the day, Governor Nelson Rockefeller dispatched his plane to pick him up.)

In his remarks, King referenced the recent assault in Alabama and outlined his peaceful strategy for countering similar attacks. “We are not violent,” he said. “We have love in our hearts for those who hurt us … We must let people know we will wear you down by our capacity to suffer. We will meet your capacity to inflict punishment by our capacity to endure punishment.” At the same time, he stressed that “if America is to remain a first-class nation, she can no longer afford to have second-class citizens.”

King’s words in Albany directly foreshadowed those he would speak two years later in Washington when he said that “America is essentially a dream, a dream of a land where men of all races, creeds, and nationalities can live together as brothers.”

The audience interrupted King several times with deafening applause, recalled Dees, who went on to become the pastor of Wilborn Temple. “It was something to witness, I’ll tell you,” Dees said. “King was a great orator, even though he was young and not very well known outside the South at that point. He had a drive and a presence that was different from other preachers I’d heard.”

“I viewed the speech as a wake-up call to Albany,” remembered attendee Peter Pryor, then a young lawyer who went on to found the city’s Urban League. As he told the Times Union reporter, “It was a reminder by King that what was happening in the South existed in a more latent form in communities like Albany in the North.”

“An ugly relic of a dark past“

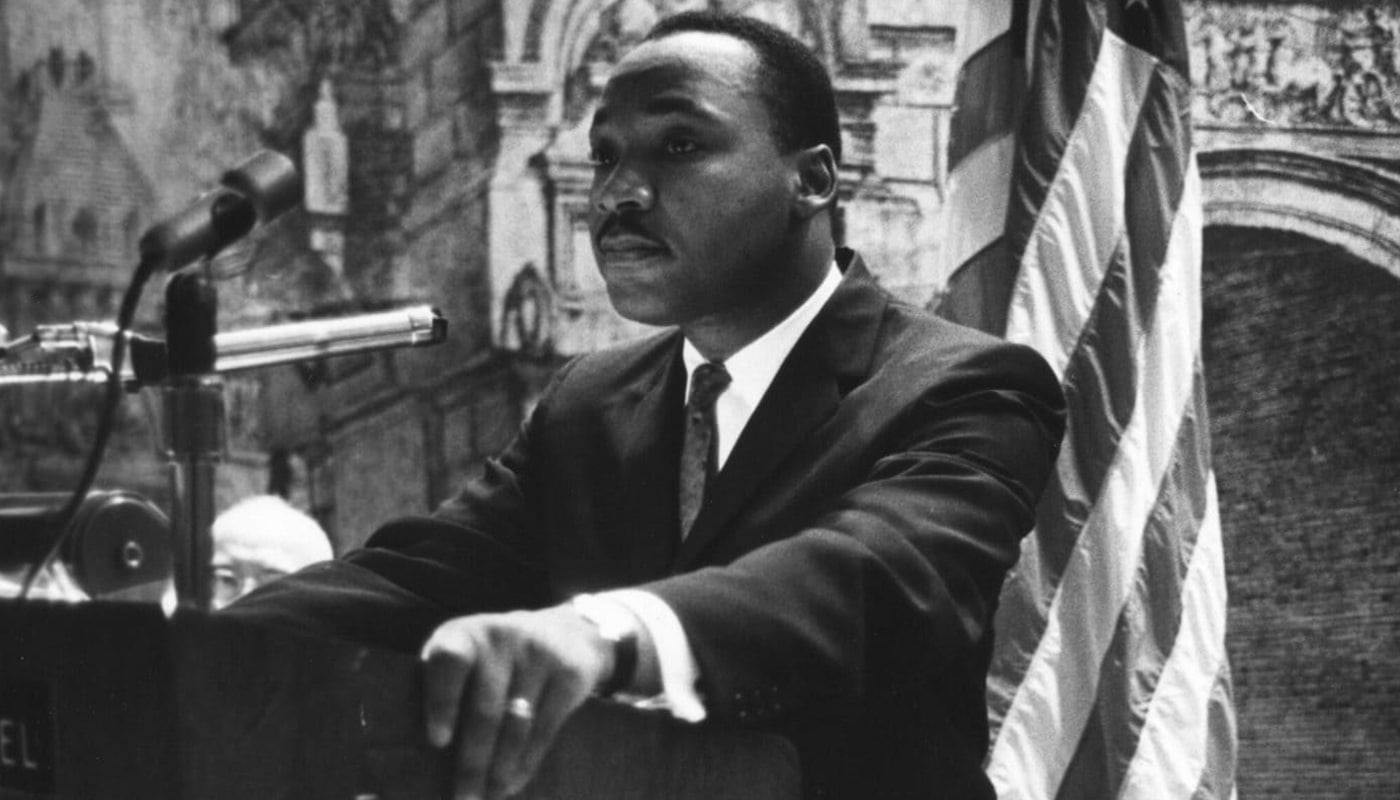

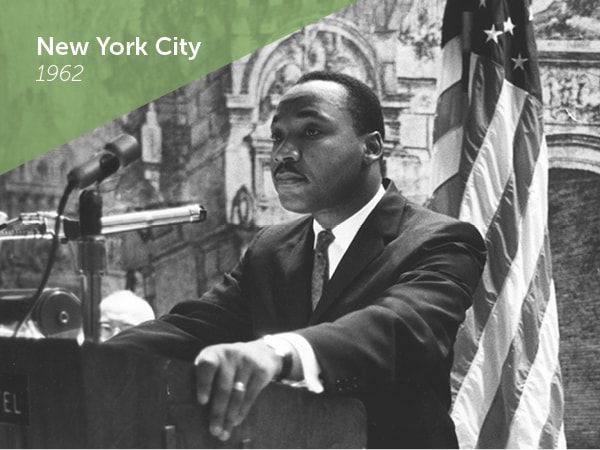

A year later, on September 12, King returned to New York to be keynote speaker at a Manhattan event honoring the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation. When a scheduling conflict made his attendance unlikely, Governor Rockefeller again stepped up, assuring King’s appearance by making a donation to rebuild several recently fire-bombed Black churches in Georgia. (Once asked about Rockefeller’s commitment to the Civil Rights movement, King replied, “If we had one or two governors in the Deep South like Nelson Rockefeller, many of our problems could be readily solved.”)

As with his “I Have a Dream” speech, King’s remarks at the Park Sheraton Hotel stressed the importance — and failures — of Abraham Lincoln’s 1862 executive order to free the nation’s enslaved people. “The Proclamation of Inferiority has contended with the Proclamation of Emancipation, negating its liberating force,” he said.

Many of King’s sentences echoed the lyricism embodied in his Washington remarks:

- “The unresolved race question is a pathological infection in our social and political anatomy, which has sickened us throughout our history, and is still today a largely untreated disease.”

- “The imposition of inferiority externally and internally are the slave chains of today. What the Emancipation Proclamation proscribed in a legal and formal sense has never been eliminated in human terms.”

- “All Americans must enlist in a crusade finally to make the race question an ugly relic of a dark past. When that day dawns, the Emancipation Proclamation will truly be commemorated in luminous glory.”

Amazingly, someone had the prescience to record King’s speech. However, the tape sat in the New York State Archives in Albany until curators and interns poring through the vast collection in 2014 discovered a box whose masking tape label said “Martin Luther King, Jr., Emancipation Proclamation Speech, 1962.”

“So they load it into a reel-to-reel machine and up comes the voice of Martin Luther King, Jr. It’s clear as a bell,” said New York State Museum Director Mark Schaming. You can listen to King’s dramatic cadences and his words that still resound with so much relevance here.

Concern for all people facing discrimination

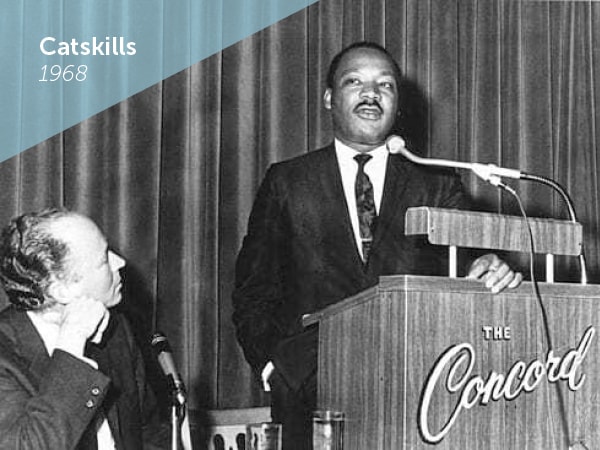

On March, 25, 1968, King made another trip to the region, one that received little notice at the time and would turn out to be his penultimate public speech. He traveled to the Concord Hotel in the Catskills to attend a convention of the Rabbinical Assembly. By then the youngest-ever Nobel Peace Prize laureate, King came to honor Rabbi Abraham Joshua Herschel, his colleague and friend who had joined him in the famous 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala.

In his brief, primarily unplanned remarks to the rabbis, King expressed his concern for all people facing discrimination, including Jewish and Black people. And he urged his listeners to take part in the upcoming Poor People’s March on Washington in order to call attention to the 40 million Americans living in poverty.

(Image: Rabbinical Assembly Archives)

King himself would not be present. Just 10 days after this third visit to the valley he was dead, victim of an assassin’s bullet.

In his final speech, the evening before his death in Memphis, Tennessee, King concluded with these fateful — but also hopeful — words: “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!”