Before the mid-1850s, Hudson Valley farms kept a cow or two to supply the family’s dairy needs. It took a scandal in New York City to turn the region into a milk mecca — and make it the birthplace of condensed milk. This product, which helped win the Civil War and lower America’s alarming infant mortality rate, owes its existence to an oft-failed inventor, a valley religious group, and the region’s many bovines.

In the early 19th century, many urban babies subsisted on milk from cows housed in unsanitary conditions near distilleries. This was convenient for liquor manufacturers: They disposed of their grain waste by feeding it to the animals. The blue-tinted liquid emerging from the cows — often whitened with plaster of Paris — was less nutritious than milk from well-fed cows.

Eventually, newspapers exposed the so-called “swill milk scandal,” which doctors determined was largely responsible for the city’s high infant mortality rate. A push began to supply fresh, pure milk. Hudson Valley farms responded by turning their meadows over to cows.

Thanks to rail lines such as the Harlem and Erie (now rail trails in Dutchess-Columbia and Orange counties), milk began flowing into Manhattan. Each morning, farmers poured their cows’ output into large tin cans with their farm name and took them to the nearest depot for pickup. Later, a returning “milk train” brought back the empties.

The milk arriving in New York was pure, but often spoiled, especially if it had traveled from the outer valley. Before the milk trains went out of business in the mid-20th century (done in by bulk containers and tanker trucks), creameries at train depots began pasteurizing and bottling the milk. That assured its freshness upon arrival.

But that was all in the future when Gail Borden, Jr., developed a product that would ensure babies received a healthy diet.

Born in central New York in 1801, Borden was a wanderer, working as a teacher, surveyor, and newspaper editor in Kentucky, Indiana, Mississippi, Texas, and Connecticut before returning east. He also was an inventor whose ideas seemed too far ahead of their time. Perhaps his most farsighted creation was an amphibious vehicle, which he dubbed the “terraqueous machine.” A combination of horse-drawn wagon and sailboat, it capsized in the Gulf of Mexico during its maiden voyage.

In his first crack at preserved foods, Borden developed the “meat biscuit,” a combination of dehydrated meat and potato baked into a cracker. Although it won a gold medal at London’s Great Exhibition in 1851, pronounced “one of the most important discoveries of the age,” Borden failed to secure a contract for the biscuit with the U.S. Army. (They said it was “not only unpalatable, but failed to appease…hunger, producing headache, nausea and great muscular depression.”) Borden had even less success with his ideas for fruit juice concentrates (think Kool-Aid) and a precursor to freeze-dried coffee.

The story goes that on his homeward voyage from the exhibition in England, Borden witnessed the deaths of several children who had drunk tainted milk. Soon, he set his sights on halting this all-too-common tragedy. He got a big boost from the Mount Lebanon Colony of Shakers, the largest settlement of this religious group organized in America in the 1780s. Learning of the colony’s success at distilling herbs while retaining medicinal potency, Borden ventured to their Columbia County settlement in 1853. The Shakers let him in on their secret: A vacuum pan, which allowed liquids to boil at a lower temperature, preventing them from burning.

Borden was sure he could employ the same technology to condense milk that would stay fresh and taste good — with the addition of a little sugar — for longer periods. The Shakers granted him permission to experiment with the pan. The process worked like a charm, and Borden patented it in 1856.

Borden tried producing and selling the new product on his own in Connecticut but soon ran out of money. Fortune smiled on him when he made the chance acquaintance of investor Jeremiah Milbank. Hearing the idea, Milbank agreed to bankroll production.

In 1861, cans of Borden’s condensed milk began rolling out of a newly constructed factory in Wassaic, Dutchess County. The region’s cows, housed in sanitary conditions per Borden’s strict regulations, supplied the main ingredient.

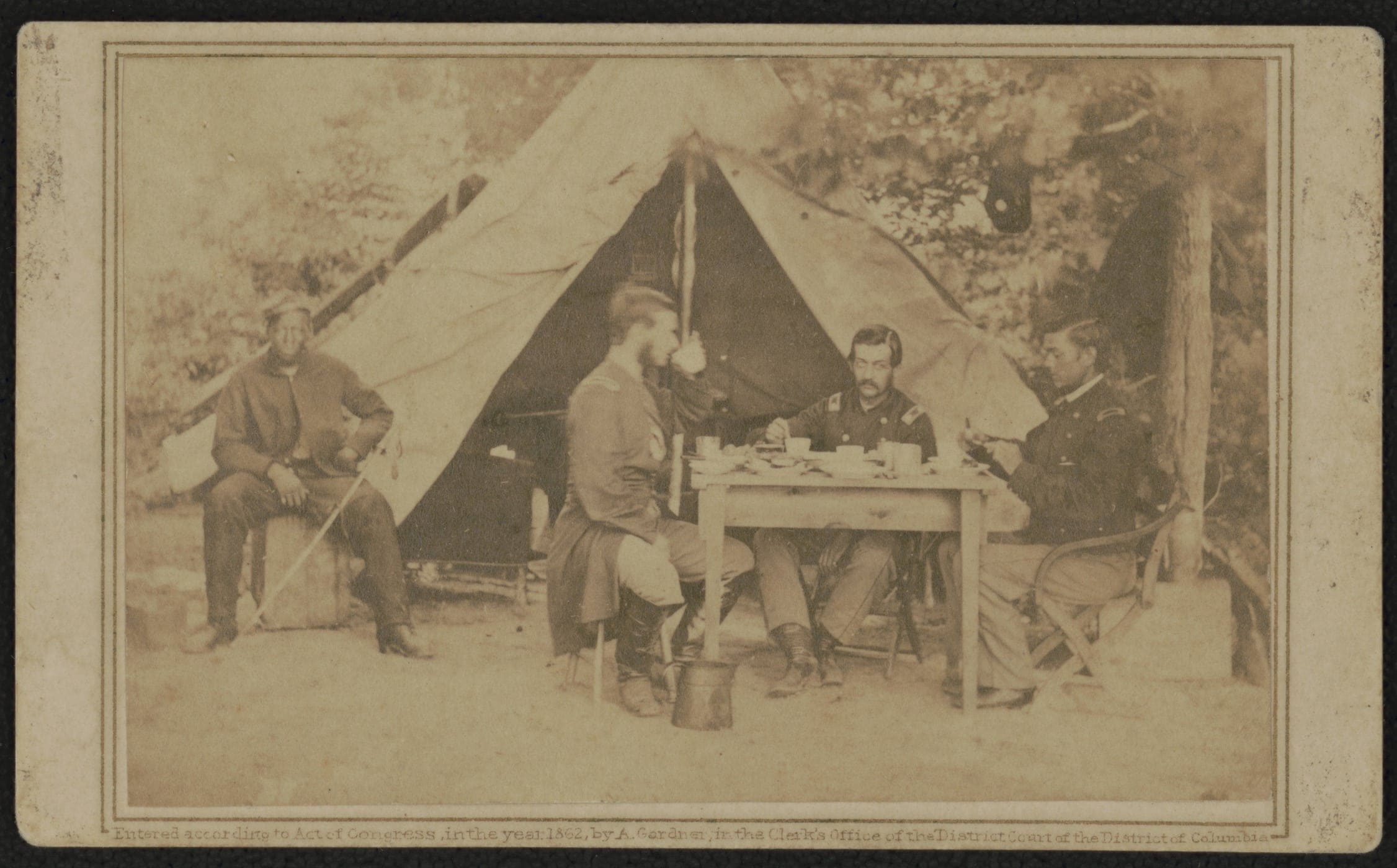

The timing couldn’t have been better. In the midst of the Civil War, the U.S. Army was in desperate need of non-perishable, easy-to-move rations for its troops.

Now they clamored for Borden’s invention, and the Wassaic factory went into overdrive to meet the demand. From producing 16,000 quarts a month in 1862, it reached a high of 14,000 quarts a day in 1863, requiring the milk from every cow within a 15-mile radius of the plant. Best of all, soldiers liked the milk’s taste, and it helped keep them in fighting shape by providing 1,300 calories of good nutrition from each 10-ounce airtight can.

Some historians credit the North’s distinct advantage in food technology with being a deciding factor in the Civil War’s outcome, and they specifically cite Gail Borden’s role in advancing that technology. As Dutchess County historian Henry Noble MacCracken put it, “Apart from the soldiers’ service, [the county’s] greatest contribution to the Civil War was this condensed milk from Wassaic. Its freedom from bacteria…must have saved many lives.” After the war, condensed milk started reaching the nation’s households and helped lower infant mortality.

The epitaph on Gail Borden’s grave in New York City’s Woodlawn Cemetery perfectly sums up his deeply American story: “I tried and failed. I tried again and again and succeeded.” True, with a little help from Columbia County’s Shakers and a whole lot of Hudson Valley cows.