Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, published in 1962, is considered the bible of the modern environmental movement. Its compelling and science-based account of the horrors inflicted on Earth’s entire ecosystem by the pesticide DDT galvanized people to take a stand against this poison, leading to its prohibition in 1972.

Carson (1907-1964) remains a heroine of environmentalists around the globe, but did she have a Hudson Valley connection? Yes. You could say she’s responsible for the sloop Clearwater. In a 1998 radio interview, Clearwater godfather and folksinger Pete Seeger, an environmental icon himself, he was asked how he came up with the idea for the boat:

It was Rachel Carson’s famous book Silent Spring. I read it in The New Yorker, in installments. Up to then, I’d thought the main job to do is help the meek inherit the Earth. And I still, that’s a job that’s got to be done. But I realized if we didn’t do something soon, what the meek would inherit would be a pretty poisonous place to live.

And so I made almost a 180-degree turn, started reading books like The Population Bomb by Paul Ehrlich, or The Poverty of Power by Barry Commoner. I’m a readaholic. And I was reading a book about the sailboats that sailed here, oh, all during the 19th century. Alexander Hamilton wrote one of the Federalist Papers on his way to Poughkeepsie in a sloop, where they were arguing whether or not to sign the Constitution idea and agree to it.

Well, I write a letter to my friend: wouldn’t it be great to build a replica of one of these? Probably cost $100,000. Nobody we know has that money, but if we got 1,000 people together we could all chip in. Maybe we could hire a skilled captain to see it’s run safely and the rest of us could volunteer.

And three years later [1968] the sloop Clearwater was built up in Maine, and I helped sail it down with Don McLean and a batch of other singers. And now it takes school kids out. It’s not a rich man’s cruise boat. Two or three times a day it takes groups of 50 school kids out, teaches them what makes rivers dirty and what’s got to be done to clean them up. Of course, people say what can a sailboat do? It can’t do much except bring people together. But when people come together, that’s when miracles happen, right?

Rachel Carson (Photo: orionpozo on Flickr (CC BY-2.0))

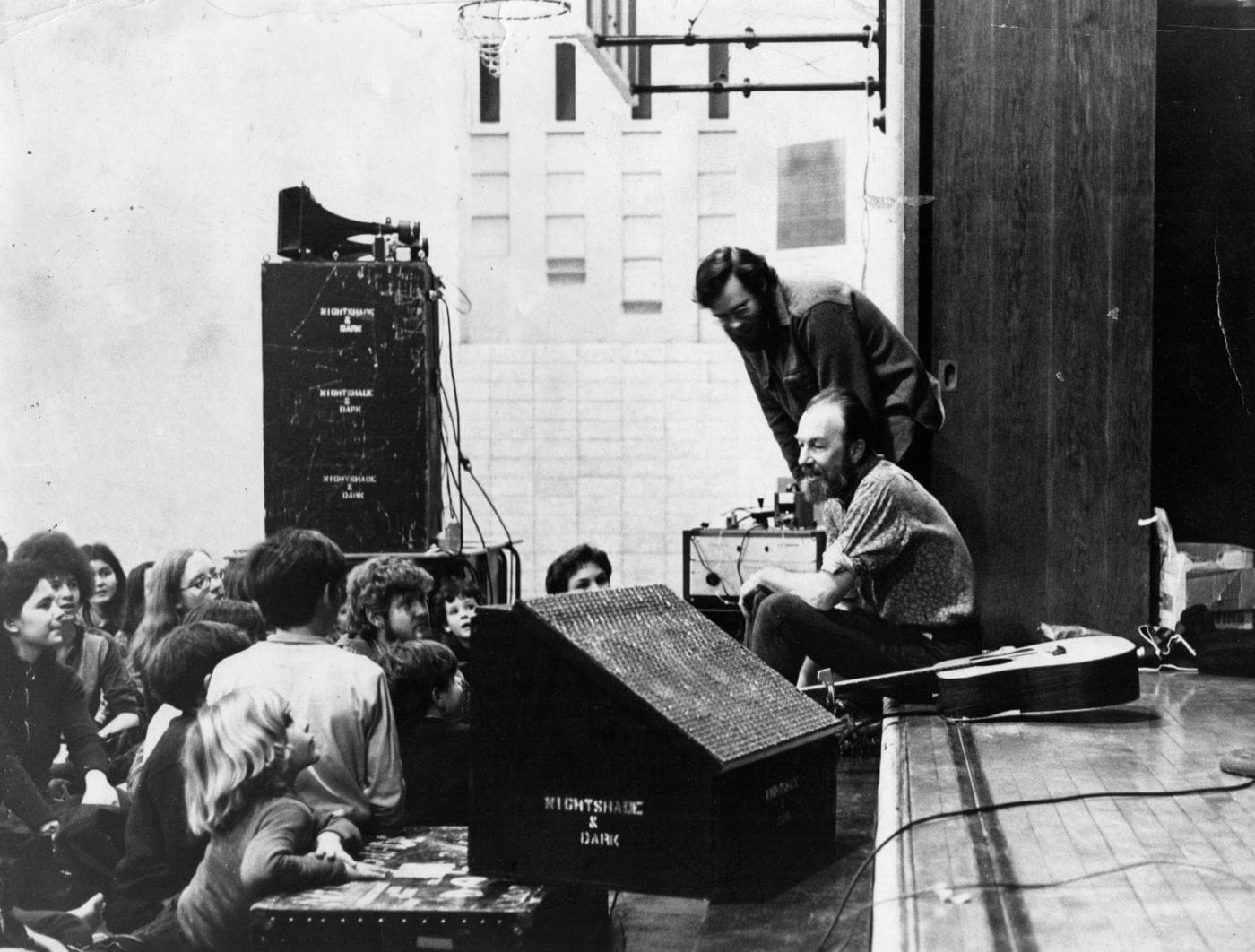

Pete Seeger, Benefit for Emmaus House, College of NEW ROCHELLE, 1972 (Photo: Jim Forest on Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND-2.0))

Pete Seeger at Newport Folk Festival, 2011 (Photo: Jennifer Jameson on Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0))

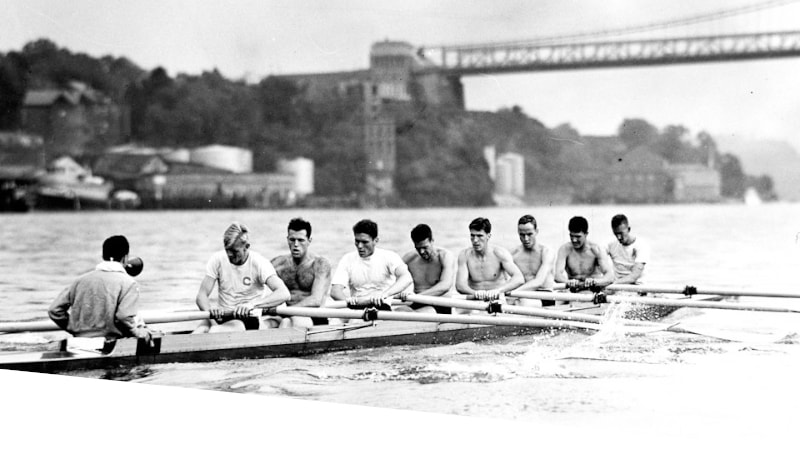

Sloop Clearwater off Manhattan (Photo: WorldIslandInfo on Flickr (CC BY-2.0))

Postscript: In 1970, Seeger and the Clearwater crew sailed to Washington, D.C., to hold a forum on the need for Congress to pass a Clean Water Act. Seeger not only presented the legislators with a petition bearing hundreds of thousands of signatures, but delivered an impromptu concert. Although it took two more years for the act to become law, Seeger’s appearance, courtesy of the boat inspired by Rachel Carson, is considered a “watershed” moment leading to its passage.